Artefact or object:

Description:

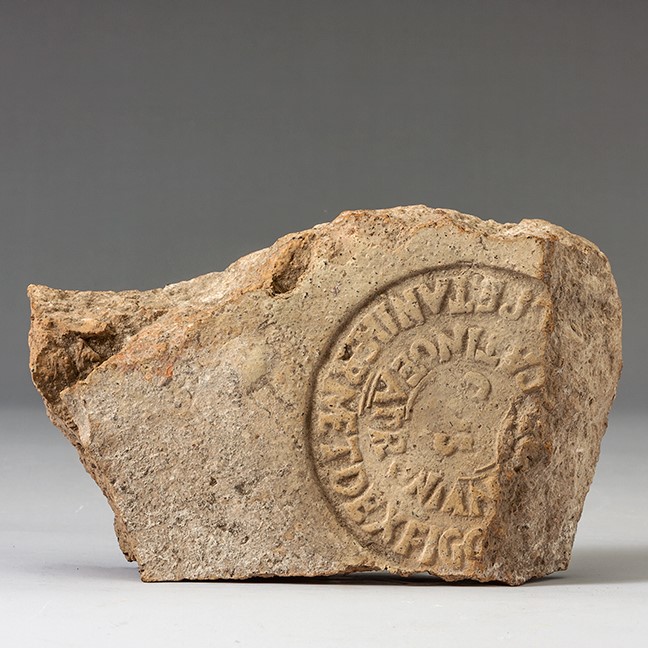

Roman Brick-Stamps

Introduction by J.R. Green

The development of construction in concrete with brick facing that occurred under the early Julio-Claudians prompted an enormous expansion in the Roman brick industry. Events such as the great fire in Rome in AD 64, with the consequent rebuilding, and then the extensive urban construction programmes in both Rome and Ostia under Trajan and Hadrian (AD 98-134), not to mention individual projects like Hadrian’s large Villa at Tivoli, brought building activities and their ancillary industries to their peak. During this period more and more bricks were stamped with the names of the brickyards and their owners, and in many cases too, with the date of manufacture, that is, with the names of the consuls for the year.

A fundamental study of brick-stamps was made by H. Bloch in a series of articles “I bolli laterizi e la storia edilizia romana” in Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma 64, 1936, 141-225; 65, 1937, 83-187; 66, 1938, 61-221. The basic collection of brick-stamps remains Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum XV, 1, but Bloch’s “The Roman Brick-Stamps Not Published in CIL XV, 1”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 56-57, 1947, 1-128 together with “Indices to Roman Brick-Stamps”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 58-59, 1948, 1-104 (both these articles reprinted in book form, Rome 1967) added many further examples as well as providing invaluable indices to the whole. Since then there have been many publications of stamped bricks from key areas of the city of Rome, principally by Bianchi and Steinby, but note some from palaces on the Palatine by E. Bukowiecki and U. Wulf-Rheidt, “I bolli laterizi delle residenze imperiali sul Palatino a Roma”, Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 121, 2015, 311-482 (and note http://arachne.uni-koeln.de/drupal/?q=en/node/392). For a publication of the largest collection of brick-stamps outside Italy, see J.P. Bodel, Roman Brick Stamps in the Kelsey Museum (Ann Arbor 1983).

Among more recent publications one may note the efforts towards a broader level of interpretation, including T. Helen, Organization of Roman Brick Production in the First and Second Centuries AD. An Interpretation of Roman Brick Stamps (Helsinki 1975); P. Setälä, Private Domini in Roman Brick Stamps of the Empire. A Historical and Prosopographical Study of Landowners in the District of Rome (Helsinki 1977); Chr. Bruun (ed.), Interpretare i bolli laterizi di Roma e della Valle del Tevere: produzione, storia economica e topografica (Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae 32, 2005). There is also now a good, compact but well-documented introduction by E. Bianchi, I bolli laterizi nella storia edilizia di Roma (Rome 2012) and see the same aurthor’s “L'industria del laterizio e i bolli doliari a Roma in età imperiale”, in M. Milella, S. Pastor, and L. Ungaro (eds), Made in Roma. Marchi di produzione e di possesso nella società antica (Rome 2016) 18-20. There are also interesting interpretive articles by Olcese and Steinby in W.V. Harris (ed.), The Inscribed Economy. Production and Distribution in the Roman Empire in the Light of Instrumentum Domesticum (JRA Suppl. 6, Ann Arbor 1993).

For historians interested in the roles of individuals, see F. Chausson, “Des femmes, des hommes, des briques: prosopografie sénatoriale et figlinae alimentant le marché urbain”, Archeologia Classica 56, 2005, 225-267. As one example, the incredibly wealthy and influential Matidia the younger, aunt of the emperor Antoninus Pius, gained some of her income from brickyards: see e.g. M.-O. Charles-Laforge, “Patrimoines et héritages des femmes à Rome: l’exemple des princesses antonines”, in: C. Chillet, C. Courrier et L. Passet (eds), Arcana Imperii. Mélanges d’histoire économique, sociale et politique, offerts au Professeur Yves Roman (Paris 2015) 233-274. On Roman naming systems and their use in stamps, there is a helpful introductory article by T.P. Wiseman, “Tile-Stamps and Roman Nomenclature”, in: A. McWhirr (ed.), Roman Brick and Tile. Studies in Manufacture, Distribution and Use in the Western Empire (British Archaeological Reports 68, Oxford 1979) 221-226.

One of the most obvious uses of brick-stamps to the student of Roman architecture is their value for dating the buildings of which they form part. The best known case is perhaps that of the Pantheon in Rome which until 1892 was believed to be contemporary with the porch which bears an inscription recording its erection by Agrippa and its dedication in 27 BC. The brick-stamps made it clear that the building as we have it is Hadrianic. It is well worth consulting L.C. Lancaster’s “Conclusions” in Arqueología de la construcción, V. Man-made materials, engineering and infrastructure (Anejos AEsp, 88, 2016) 343-352. As well as discussing the presentations by other contributors, she stresses the importance of putting the results of construction analyses into a broad cultural context in order to highlight their relevance to those outside our discipline.