Acquisition number: 1964.01

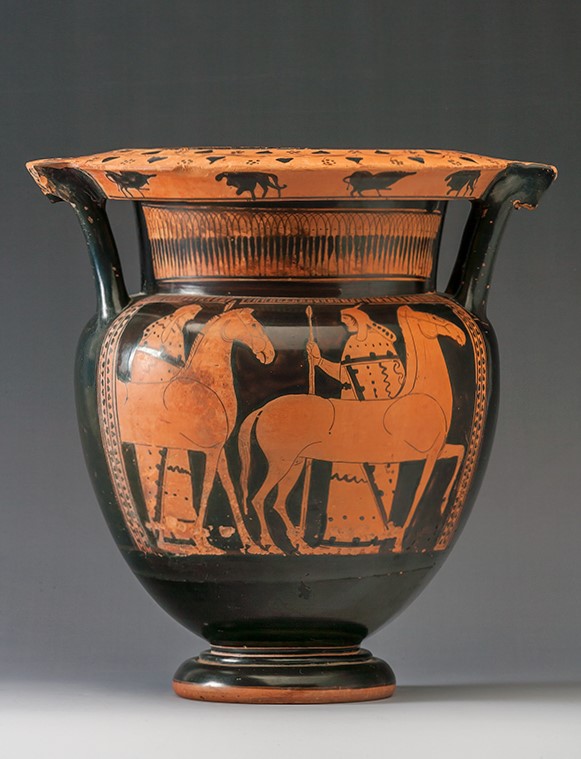

Attic Red-Figure Column-Krater.

A: Two men in Thracian dress with their horses. B: Three youths wearing himatia.

On the top of the lip is a garland of ivy with dot helichryse; palmettes on the handle flanges. On the outer edge of the lip is a frieze of boars and lions in silhouette technique. The neck is decorated on side A with lotus buds linked in groups of five; it is black on B. Both scenes have ivy side borders and tongues above. A line of added red, now worn, runs around the vase at the level of the bottom on the scenes. There are incised lines about the fillet between body and foot; the lower part of the foot and the underside are reserved. There is a glaze wash inside the vase.

On side A, both men wear the cap known as an alopekis (fox-skin) on their heads and a stiff sort of cloak known as a zeira over a heavy decorated chiton. One cannot see their boots. The figure on the left is bearded and he is therefore older, and the way that the other looks round to him shows that, whoever else he may be, he is a respected, senior figure. His beard is shown as light in colour, but one cannot say whether that means that it is grey, or (perhaps more likely) fair or blond in colour. Both figures carry lances (the head of the older man’s appears by his horse’s head) and the young man carries twin lances (as he should), as one can see from the lower part even if the painter seems to have combined them into a single element above his hand.

Title: Attic Red-Figure Column-Krater - 1964.01

Acquisition number: 1964.01

Attribution: Painter of the Louvre Centauromachy.

Author or editor: J.R. Green

Culture or period: Attic Red-Figure.

Date: c. 430 BC.

Material: Clay - Terracotta

Object type: Pottery - Red-figure

Dimensions: 286mm (w) × 354mm (h)

Origin region or location: Greece

Origin city: Athens.

Display case or on loan: 3

Keywords: Greek, Attic, Red Figure, Painter of the Louvre Centauromachy, Thrace

Sotheby (London), Sale Cat., 24 February 1964, no. 95 with ill. at p. 31; J.D. Beazley, Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters (Oxford 1971) 449, 33 bis; J.R. Green with B. Rawson, Catalogue of Antiquities in the Australian National University, A.N.U. (Canberra, 1981) 41-42; F. Lissarrague, L’autre guerrier. Archers, peltastes, cavaliers dans l'imagerie attique (Paris-Rome 1990) 213 n.74, 302 no. C 51. T.H. Carpenter, with T. Mannack and M. Mendonca, Beazley Addenda, 2nd edition (Oxford 1989): 328; Beazley Archive Pottery Database 276100.

1964.01

Attic Red-Figure Column-Krater

Purchased. Ht 35.4cm; diam. (lip) 28.6cm.

Intact and in good condition save for some slight wear of the surface in places.

A: Two men in Thracian dress with their horses. B: Three youths wearing himatia.

On the top of the lip is a garland of ivy with dot helichryse; palmettes on the handle flanges. On the outer edge of the lip is a frieze of boars and lions in silhouette technique. The neck is decorated on side A with lotus buds linked in groups of five; it is black on B. Both scenes have ivy side borders and tongues above. A line of added red, now worn, runs around the vase at the level of the bottom on the scenes. There are incised lines about the fillet between body and foot; the lower part of the foot and the underside are reserved. There is a glaze wash inside the vase.

On side A, both men wear the cap known as an alopekis (fox-skin) on their heads and a stiff sort of cloak known as a zeira over a heavy decorated chiton. One cannot see their boots. The figure on the left is bearded and he is therefore older, and the way that the other looks round to him shows that, whoever else he may be, he is a respected, senior figure. His beard is shown as light in colour, but one cannot say whether that means that it is grey, or (perhaps more likely) fair or blond in colour. Both figures carry lances (the head of the older man’s appears by his horse’s head) and the young man carries twin lances (as he should), as one can see from the lower part even if the painter seems to have combined them into a single element above his hand.

The painter’s technique is clearly evident on this vase. The scene on A was sketched out before painting and in this case a glancing light will reveal that the head of the right-hand horse was originally planned to be lower. The first painted outline of the scene is distinguishable in a heavier paint than the in-filling, and indeed one may notice that the blacking-in is incomplete about the feet of the left youth on the reverse. The painter used relief line for internal detail on both scenes but there is no relief contour. On preliminary sketch, see the fundamental analysis by P.E. Corbett, Journal of Hellenic Studies 85, 1965, 16-28, and then the more recent article (with good illustrations) by M. Boss, “Preliminary Sketches on Attic Red-Figured Vases of the Early Fifth Century B.C.”, in: J.H. Oakley, W.D.E. Coulson and O. Palagia (eds), Athenian Potters and Painters: The Conference Proceedings (Oxford 1997) 345-351.

An interesting aspect of the scene on A is the relationship between the scene and the border. Only half the left-hand horse is shown, to our eye disappearing behind the frame, but the spear of its owner is superimposed on the frame. This apparent contradiction is not unusual in Greek vase-painting. The ‘frame’ is simply a border to surface decoration and there is no real concept at this stage in ancient art of a frame about a view of a scene beyond, in the sense of a window- or picture-frame. For something of a discussion and an attempt to provide a classification of ancient attitudes, see J. Hurwit, “Image and Frame in Greek Art”, American Journal of Archaeology 81, 1977, 1-30; also, on somewhat different issues, his “A Note on Ornament, Nature, and Boundary in Early Greek Art”, Bulletin Antieke Beschaving 67, 1992, 63-72. More recently: M. Maaß, “Zerteilte und abgeschnittene Bilder”, in: W. Raeck (ed.), Figur und Raum in der frühgriechischen Flächenkunst (Wiesbaden 2017) 55-62; C. Marconi, “The Frames of Greek Painted Pottery”, in: V. Platt and M. Squire (eds), The Frame in Classical Art. A Cultural History (Cambridge 2017) 117-153.

The vase, which may be dated about 430 BC, was attributed by Beazley to the Painter of the Louvre Centauromachy. (On the painter, see the lists and references in J.D. Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters [2nd ed., Oxford 1963] 1088-l094 and 1682-1683, and Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters [Oxford 1971] 449-450.) He attributed a total of 117 pieces to this painter of which 43 are column-kraters, 34 bell-kraters and 16 pelikai. Apart from the centauromachy which gives the painter his name, his vases show athletes, Bacchic scenes and warriors leaving home. He painted Thracians on four other known vases (Beazley’s nos 33, 34, 34 bis and 87 bis; see also below) and a scene of Orpheus and the Thracians on another (40). The Thracians are easily recognizable from their national dress of long embroidered cloaks and fox-skin caps.

Compare too the similar scene on a near-contemporary column-krater possibly by our painter in Bologna, together with Riccioni’s discussion of it in Archeologia Classica 5, 1953, 248-251 = Scritti … Riccioni (Bologna 2000) 41-45; J.D. Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters (2nd ed., Oxford 1963) 1095, 3. This long, heavy version of the cloak, the zeira, is repeated for example on the neck-amphora by the Phiale Painter in Altenburg, Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum pl. 49, 1, Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters 1015, 2.

At the same time it is worth noting that Attic red-figure column-kraters were not-uncommonly imported into Thrace: e.g. S. Vasileva, “Column-kraters of the 5th Century BC from Thrace (based on finds from Bulgaria)”, in: G.R. Tsetskhladze et al. (eds), The Bosporus: Gateway between the Ancient West and East (1st Millennium BC–5th Century AD) (BAR Int. Series 2517, Oxford 2013) 129-143.

On depictions of Thracians more generally, see out of a large bibliography K. Zimmermann, “Thraker-Darstellungen auf griechischen Vasen”, in: R. Vulpe (ed.), Actes du IIe Congrès international de thracologie, Bucarest 4 - 10 septembre 1976, i: Histoire et archéologie (Bucharest 1980) 429-446; W. Raeck, Zum Barbarenbild in der Kunst Athens (Bonn 1981) 67-100; H.A. Shapiro, “Amazons, Thracians and Scythians”, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 24, 1983, 105-114 (with refs.), and E.G. Pemberton, “An Early Attic Red-Figured Calyx-Krater from Ancient Corinth”, Hesperia 57, 1988, 227-235; D. Tsiafakis, “The Allure and Repulsion of Thracians in the Art of Classical Athens”, in: B. Cohen (ed.), Not the Classical Ideal. Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art (Leiden 2000) 364-389. There is also a useful overview by P. Schirripa, “L’image grecque de la Thrace entre barbarie et fascination. Pour une remise en question”, in I Traci tra geografia e storia (Aristonothos 9, 2015) 15-53.

A key issue is whether we see here ‘real’ Thracians or Athenian horsemen dressed in Thracian costume. It was fashionable from the later sixth century onwards for young Athenian élite to wear clothing of Thracian style when riding as cavalrymen. A good example of an aristocratic young Athenian dressed in this way is the rider on the inside of the well-known cup by Euphronios in Munich (8704 [2620], Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters 16, no. 17; E. Simon, Die griechischen Vasen [Munich 1976] pl. 107; Euphronios pittore ad Atene nel VI secolo a.C. [Milan 1991] 191-196 no. 41 with colour ills), where he wears a petasos and is surely Greek. Compare too the cup by the Foundry Painter in the Villa Giulia (inv. 50407): Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters 402, 24; E. Simon, Die griechischen Vasen (Munich 1976) pl. 159, or the young cavalryman on the interior of the cup in the Louvre by the Pistoxenos Painter, Lissarrague, Greek Vases. The Athenians and their Images (New York 2001) 56 fig. 43, datable about 470-460 BC.There are also pictures of them in the process of submitting their horses for examination before the boule, the so-called dokimasia. In our case, however, there is no hint of any of this and it seems safe to conclude that we are in fact dealing with a depiction of Thracians (as one might also suppose if the beard of the older man is in fact shown as blond).

The best discussion of the problem is that by F. Lissarrague, L’autre guerrier. Archers, peltastes, cavaliers dans l'imagerie attique (Paris-Rome 1990) 210-231. On depictions of the dokimasia, see G. Körte, “Dokimasie der attischen Reiterei”, Archäologische Zeitung 38, 1880, 177-181; H.A. Cahn, “Dokimasia”, Revue Archéologique 1973, 3-22; id., “Dokimasia II”, in: E. Böhr and W. Martini (eds), Studien zu Mythologie und Vasenmalerei. Festschrift für Konrad Schauenburg (Mainz 1986) 91-93. See further Braun, Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung 85, 1970, 129-269; Kroll, Hesperia 46, 1977, 83-140; G.R. Bugh, Hesperia 67, 1998, 81-90; and of course Aristotle, AthPol 49.

Orpheus was often depicted in Thracian dress at this period and for an excellent discussion of the phenomenon, see F. Lissarrague, “Orphée mis à mort”, Musica e Storia 2, 1994, 269-307. Note in particular the name vase of Orpheus Painter, Berlin 3172, Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters 1103, 1, Robertson, The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens (Cambridge 1992) 217 fig. 125. In addition to the entry on Orpheus in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, see M. Schmidt, “Bemerkungen zu Orpheus in Unterwelts- und Thrakerdarstellungen”, in: P. Borgeaud (ed.), Orphisme et Orphée. En l'honneur de J. Rudhardt (Geneva 1991) 31-50.

Thracians and things Thracian had a prominent place at Athens. In addition to Orpheus, there were other prominent mythical musicians such as Thamyras, Musaeus and Eumolpus. Several well-known myths were set in Thrace, many of them important to Tragedy and therefore very much in the public eye: Phineus, Lykourgos, Thamyras and Tereus. With regard to the Tereus story, one remembers not only the plays by Sophocles and Philocles but Alkamenes’ statue on the Athenian Akropolis (still extant) of Prokne preparing to kill her son Itys. There are Thracians or cavalrymen dressed as Thracians on the Parthenon frieze, and possibly on the metopes. One recalls that at the beginning of Plato’s Republic (328A), there had been a celebration of the Thracian goddess Bendis in Piraeus. There is a good survey of all this in D.Tsiafakis, ΗΘράκηστηναττικήεικονογραφίατου 5ουαιώναπ.Χ. (Komotini 1998). At a more practical level many nurses in Athens were Thracian, indeed one might say they were typically Thracian, and they must have had a marked influence on their young charges. And then Kleophon, the politician prominent in the later part of the fifth century, was said to have a Thracian mother – and it was a way of implying that he did not have a good background: E. Vanderpool, “Kleophon”, Hesperia 21, 1952, 114-115.

See the South Italian antefix in the ANU collection (1979.08) that seems to represent the goddess, and the references given in the catalogue. Note also R.R. Simms, “The Cult of the Thracian Goddess Bendis in Athens and Attica”, The Ancient World 18, 1988, 59-76; C. Montepaone, “Bendis tracia ad Atene: l’integrazione del ‘nuovo’ attraverso forme dell’ideologia”, AION 12, 1990, 103-121 = Mélanges Pierre Lévèque vi (AnnLit Besançon 463, 1992) 201-220; C. Planeaux, “The Date of Bendis’ Entry into Attica”, Classical Journal 96:2, 2000-2001, 165-192. There are good notes from a socio-historical perspective by R. Garland, Introducing New Gods: The Politics of Athenian Religion (London 1992) 111-114.

On Thracians in Athenian art generally, see C. Marcaccini, “Il ruolo dei Traci nell’immaginario greco di V-IV sec. a.C. Tra storiografia ed iconografia”, Rivista storica dell'antichità 25, 1995, 7-53. Although she is not particularly concerned with the relationship between the performance of tragedy and scenes on pottery, Tsiafakis’s excellent book (see above) examines Thracian themes and their depiction in Attic red-figure vase-painting. On the Tereus myth in art, see in particular K. Stähler, “Prokne: eine Mythengestalt in Drama und Skulptur klassischer Zeit”, in: S. Gödde und T. Heinze (eds), Skenika: Beiträge zum antiken Theater und seiner Rezeption. Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von Horst-Dieter Blume (Darmstadt 2000) 175-188, and L. Chazalon, “Le mythe de Térée, Procnè et Philomèle dans les images attiques”, Mètis ns 1, 2003, 119-148. A good recent treatment of Sophocles’ play is that by D. Fitzpatrick, “Sophocles’ Tereus”, Classical Quarterly 51, 2001, 90-101; in his discussion of the myth, he also makes good use of the visual evidence. The topic of Thracians on the Parthenon is much discussed (see in particular figures 2-7 of the South Frieze): e.g. I. Mader, “Thrakische Reiter auf dem Fries des Parthenon?”, in: Fremde Zeiten. Festschrift für Jürgen Borchhardt (Vienna 1996) 59-64. It seems, rather, to be personal costume of the kind mentioned above. Note also what T. Stevenson has to say: “Cavalry Uniforms on the Parthenon Frieze?”, American Journal of Archaeology 107, 2003, 629-654.

The young men on the other side of the vase are of a kind repeated in Attic and South Italian vase-painting to the point of banality, but it is worth bearing in mind that they are depicted as being of good family, as is made clear by the form of their dress, the heavy himation which covers the left arms and shoulder, and by the fact that they carry staffs, much as our immediate ancestors might have carried walking-sticks. (Workmen wore short, sleeved tunics which gave them much greater freedom of movement.) On their role in vase-painting, see for example C. Isler Kerényi, “Anonimi ammantati”, in: Studi sulla Sicilia occidentale in onore di Vincenzo Tusa (Padua 1993) 93-100; M. Franceschini, “Mantle Figures and Visual Perception in Attic Red-Figure Vase Painting”, in: Jacobus Bracker & Martina Seifert (eds), Visuelle Narrative – kulturelle Identitäten (= Visual Past 3.1, Hamburg 2016) 163-198; ead., Attische Mantelfiguren. Relevanz eines standardisierten Motivs der rotfigurigen Vasenmalerei (Rahden/Westf. 2018).

Sotheby (London), Sale Cat., 24 February 1964, no. 95 with ill. at p. 31; J.D. Beazley, Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters (Oxford 1971) 449, 33 bis; J.R. Green with B. Rawson, Catalogue of Antiquities in the Australian National University, A.N.U. (Canberra, 1981) 41-42; F. Lissarrague, L’autre guerrier. Archers, peltastes, cavaliers dans l'imagerie attique (Paris-Rome 1990) 213 n.74, 302 no. C 51. T.H. Carpenter, with T. Mannack and M. Mendonca, Beazley Addenda, 2nd edition (Oxford 1989): 328; Beazley Archive Pottery Database 276100.