Title: Denarius of Marcus Brutus - 1972.01

Acquisition number: 1972.01

Author or editor: Beryl Rawson

Culture or period: Roman Republic

Date: 59 or 54 BC

Material: Metal - Silver

Object type: Coins - Roman

Dimensions: 17mm (w)

Origin region or location: Italy

Origin city: Rome

Display case or on loan: 5

Keywords: Coin, denarius, Roman, Republic, Brutus

Sear, D.R., Roman Coins and their Values 5 vols (London, Spink, 2000-2014) 398; Crawford, M., Roman Republican Coinage 2 vols (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2011) 433/2 and pl. LII.10; Sydenham, E. A. The Coinage of the Roman Republic (London, Spink, 1952; (Sanford J. Durst repr. 1976) 907 and pl. 25; Seaby, H.A., Roman Silver Coins (London, B.A. Seaby, 1967) Junia 30; Grueber, H.A., Coins of the Roman Republic in the British Museum 3 vols (London, The Trustees of the British Museum, 1910; rev. edn London, 1970) I. 3864-7.

Cerutti, S., ‘Brutus, Cyprus and the coinage of 55 B.C.’, American Journal of Numismatics 5/6 (1993-94), 69-87. A. Raubitschek ‘The Brutus statue in Athens’, Atti del Terzo Congresso Internazionale di Epigrafia Greca e Latina 1957 (Rome 1959) 15-21.

1972.01

Denarius of Marcus Brutus

4.107 g. c. 59 or 54 BC

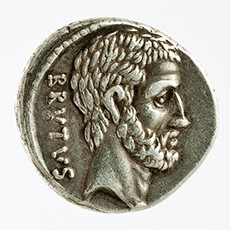

Obv.: Head of L. Iunius Brutus r., bearded. To left, BRVTVS (downwards). Border of dots.

Rev.: Head of C. Seruilius Ahala r., bearded. To left, [AHALA] (downwards). Border of dots.

Brutus claimed descent from both the early republican heroes commemorated on this coin. (See Cicero Ad Atticum 13.40; Plutarch Brutus 1.) Lucius Iunius Brutus led the expulsion of the last king of Rome (Tarquinius Superbus) and helped establish the Republic, of which he was first consul (509 BC). Gaius Seruilius Ahala killed a fellow-citizen who was suspected of aiming at supreme power for himself (439 BC) because he distributed food to the people to relieve a famine. Brutus’ mother was a Seruilia, and Brutus’ adoption by his maternal uncle gave him the right to use the Servilian name. He was proud of his ancestry and its associations with opposition to tyranny. If the earlier date (c. 59 BC) is correct, the coin may commemorate the time of Brutus’ adoption. (Cf. Cicero Ad Atticum 2.24.2 (59 BC) for reference to Brutus under both names.) Another of his coins of the same time has the legend LIBERTAS (‘freedom’) on it and commemorates the early republican Brutus (Sear 397; Crawford 433/1; Sydenham 906). These coins may express some criticism of the ‘First Triumvirate’, which was formed about this time, and may help to explain how Brutus’ name was included on the list of alleged plotters against Pompey in 59 BC (the ‘Vettius affair’). Brutus found it expedient to leave Rome in 58 BC (to join his uncle Cato on a mission to Cyprus and the East).

Crawford places the coin in 54 BC on the basis of hoard evidence, style and moneyers’ careers. He associates it with opposition to extraordinary powers for Pompey.

Coins minted by Brutus as proconsul in the East in 43-42 BC make explicit his claims to being a tyrannicide when he murdered Julius Caesar. They contain references to ‘Libertas’, to ‘L. Brutus, the first consul’, and to ‘The Ides of March’. Brutus’ own head appears on some of these, and his name appears variously as M. BRVTVS, BRVTVS, Q. CAEPIO BRVTVS, and CAEPIO BRVTVS (Crawford 500-508; Sydenham 1287-1301). It is known that the Athenians gave Brutus and Cassius a warm welcome in 44 BC and set up bronze statues to them by the side of those of Harmodius and Aristogeiton (Athenians credited with the overthrow of tyranny in Athens c. 510 BC): see Cassius Dio 47.20.4. In 1936 a fragment of an inscribed base was found in the Athenian Agora, and the restored inscription suggests that this was the base of Brutus’s statue. It records his name as Q. SERVILIVS Q. F. CAEPIO BRVTVS (thus proclaiming his membership of the families of both men on the present coin). (See Raubitschek.)

Note the beards on the faces. Beards were not commonly worn by Roman men in the late Republic or early Empire (approx. 2nd cent. BC/AD. 117). Compare the heads on imperial coins: beards returned to favour with Hadrian (see coin 66.44) and later emperors.

Sear, D.R., Roman Coins and their Values 5 vols (London, Spink, 2000-2014) 398; Crawford, M., Roman Republican Coinage 2 vols (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2011) 433/2 and pl. LII.10; Sydenham, E. A. The Coinage of the Roman Republic (London, Spink, 1952; (Sanford J. Durst repr. 1976) 907 and pl. 25; Seaby, H.A., Roman Silver Coins (London, B.A. Seaby, 1967) Junia 30; Grueber, H.A., Coins of the Roman Republic in the British Museum 3 vols (London, The Trustees of the British Museum, 1910; rev. edn London, 1970) I. 3864-7.

Cerutti, S., ‘Brutus, Cyprus and the coinage of 55 B.C.’, American Journal of Numismatics 5/6 (1993-94), 69-87. A. Raubitschek ‘The Brutus statue in Athens’, Atti del Terzo Congresso Internazionale di Epigrafia Greca e Latina 1957 (Rome 1959) 15-21.