Acquisition number: 1990.03

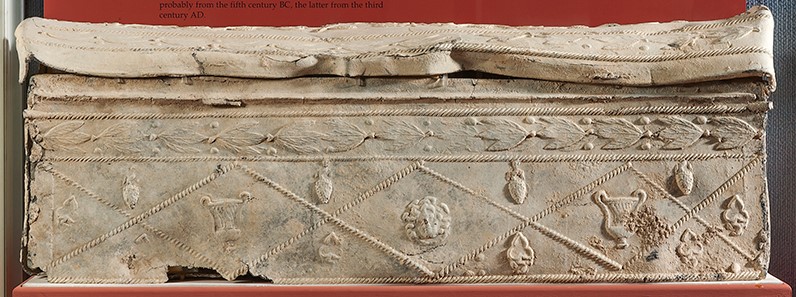

The front has an upper border of laurel leaves with fruit running in from each side and meeting to the left of centre. In the right-hand part there are traces of leaves stamped earlier and largely obscured in the later version. Below is a rope-design dividing the area into horizontal lozenges. In the central lozenge is a gorgoneion with kraters or kantharoi in those flanking it to either side. In the half-lozenges at the ends and below are vine-leaf motifs; in those above are grape-bunches. The back is similar.

On one end is an arrangement of crossed thyrsoi (?) comprising rope bands with leaves on their ends. On the other end is an architectural motif of four spirally-fluted columns with Ionic capitals, the outer two supporting an arch. The arch has a leaf-motif running along it. Between the outer pairs of columns are two vine-leaves arranged vertically.

The lid is of curved section. The upper face is divided longitudinally by rope-pattern into a broad zone at the top with narrower ones to the sides. The narrower zones reproduce the laurel motif seen on the sides (again not precisely centred), and the broader one has an undulating vine (with the grape-bunches are leaves from the same stamps as on the sides).

Title: Lead Sarcophagus - 1990.03

Acquisition number: 1990.03

Author or editor: J.R. Green

Culture or period: Roman Imperial

Date: 3rd - 4th century AD.

Material: Metal - Lead

Object type: Funerary items - Sarcophagus

Dimensions: 915mm (l) × 250mm (w) × 300mm (h)

Origin region or location: Syria

Display case or on loan: 6

Keywords: Roman, Imperial, Syrian, Funerary, Dionysos, Syria, Palestine

Sotheby (London), Antiquities, 31 May 1990, no. 412, pl. 54.

1990.03

Lead Sarcophagus

Purchased. 30 x 91.5 x 25cm.

Generally in good condition but for some minor damage along the edge of the lid and at the junctions.

The front has an upper border of laurel leaves with fruit running in from each side and meeting to the left of centre. In the right-hand part there are traces of leaves stamped earlier and largely obscured in the later version. Below is a rope-design dividing the area into horizontal lozenges. In the central lozenge is a gorgoneion with kraters or kantharoi in those flanking it to either side. In the half-lozenges at the ends and below are vine-leaf motifs; in those above are grape-bunches. The back is similar.

On one end is an arrangement of crossed thyrsoi (?) comprising rope bands with leaves on their ends. On the other end is an architectural motif of four spirally-fluted columns with Ionic capitals, the outer two supporting an arch. The arch has a leaf-motif running along it. Between the outer pairs of columns are two vine-leaves arranged vertically.

The lid is of curved section. The upper face is divided longitudinally by rope-pattern into a broad zone at the top with narrower ones to the sides. The narrower zones reproduce the laurel motif seen on the sides (again not precisely centred), and the broader one has an undulating vine (with the grape-bunches are leaves from the same stamps as on the sides).

The sarcophagus is of the so-called Syrian type. Lead sarcophagi were in fact made and used all over the Roman world, but they seem to have been particularly popular in the Syria-Palestine region where they were made in enormous quantities. Indeed the roof of the Great Mosque in Damascus is said to have be sheathed with lead made from melted-down coffins of this type. The principal centres of manufacture appear to have included Tyre, Sidon, Beirut and Jerusalem, but coffins of this type must also have been made in most of the main centres of the region. In the absence of external evidence (such as the discovery of coins in the coffin), the dates of individual examples are difficult to determine with any precision. Production was already under way in the mid-first century AD and it continued until at least the middle of the fourth. Our example should date to the third or fourth century AD.

The sheets of lead were mould-made and normally have a thickness of about 4mm. Various designs were stamped into wet sand or more probably clay to create the design. This accounts for the common irregularities of placing and layout, but at the same time for the repetition of identical forms of motif within a single design or between coffins. The ends often have an architectural motif with tetrastyle columns which gives the impression of a temple or sacred building. The long sides are usually divided by vertical column-like motifs into roughly square areas, or, as here, into a lozenge arrangement by bands of one kind or another. The open spaces have individual motifs recalling the bacchic world (like the ivy-leaves and kraters) or protective of the dead (like the Medusa head) or sometimes Judaic or Christian symbols. A motif with laurel is almost invariably used as a border.

The evocation of the world of Dionysos is seen on other of our funerary objects. Before the adoption of Christianity, it was seen as the surest way of finding happiness in the world beyond the grave, and it is significant that much early Christian iconography borrows from that of the world of Dionysos.

There are good discussions by E. von Mercklin, “Untersuchungen zu den antiken Bleisarkophagen”, Berytus 5, 1938, 27-46, A.M. Bertin, “Les sarcophages en plomb syriens au Musée du Louvre”, Revue Archéologique 1974, 43-82 (with full references to earlier studies), A.M. McCann, Roman Sarcophagi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York 1978) 143-150, and by H. Froning, “Zur syrischen Bleisarkophagen der Tyros-Gruppe”, Archäologischer Anzeiger1990, 523-535, who attempts to develop issues of chronology further by reference to the decorative traditions of other media. Note earlier M. Chéhab, “Sarcophages en plomb du Musée National Libanais”, Syria 15, 1934, 337-350 and “Sarcophages en plomb du Musée National Libanais (deuxième article)’, Syria 16, 1935, 51-72. There is a good and interesting article on one in the University Museum, Philadelphia: D. White, “Of Coffins, Curses, and Other Plumbeous Matters. The Museum’s Lead Burial Casket from Tyre”, Expedition 39:3, 1997, 3-14; also, on one in Geneva, J. Chamay, “Essai d'interprétation d'un sarcophage romain”, Genava: revue d'histoire de l'art et d'archéologie 43, 1995, 83-86.

For the architectural motif on the ends, see e.g. M. Weber, Baldachine und Statuenschreine (Archaeologica 87, Rome 1990), and, earlier, G.M.A. Richter, Catalogue of Greek and Roman Antiquities in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection (Cambridge, Mass., 1956) no. 32. More generally, J. Engemann, Untersuchungen zur Sepulchralsymbolik der späteren römischen Kaiserzeit (JbAChr, Ergh. 2, Münster 1973).

Given its length, the sarcophagus was doubtless for a young person.

Sotheby (London), Antiquities, 31 May 1990, no. 412, pl. 54.