You are here

Mouldmade Bowl - 1980.11

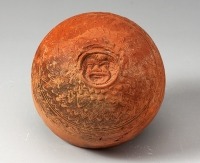

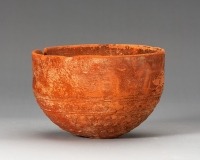

Intact but for a chip from the lip. The surface is somewhat worn in places. Much of the vase has fired a reddish colour (both glaze and clay); the clay has fairly abundant traces of mica. The vase was thrown in a somewhat worn mould. In the centre at the bottom on the outside is the mask of a slave from the comic theatre, then the main zone on the body is made up of a series of overlapping pointed leaves, and then at the lip, a zone of s-hooks between lines. The lip of the bowl was drawn up well above the level of the mould (for approximately three centimetres).

Title: Mouldmade Bowl - 1980.11

Author or editor: J.R. Green

Culture or period: Hellenistic.

Date: 2nd century BC.

Material: Clay - Terracotta

Object type: Vessels - Bowl

Acquisition number: 1980.11

Dimensions: 106mm (w) x 70mm (h)

Origin region or location: Greece

Display case or on loan: 4

Keywords: Greek, Hellenistic, Mould Made, Megarian

Charles Ede Ltd (London) Antiquities 117 (1980) no. 46; Monuments Illustrating New Comedy (3rd ed. rev. and enlarged by J.R. Green and Axel Seeberg, BICS Suppl. 50, 1995) ii, 174, 3BV 3.

1980.11

Mouldmade Bowl

Purchased. Ht 70 mm.; diam. 106 mm.

Intact but for a chip from the lip. The surface is somewhat worn in places. Much of the vase has fired a reddish colour (both glaze and clay); the clay has fairly abundant traces of mica. The vase was thrown in a somewhat worn mould. In the centre at the bottom on the outside is the mask of a slave from the comic theatre, then the main zone on the body is made up of a series of overlapping pointed leaves, and then at the lip, a zone of s-hooks between lines. The lip of the bowl was drawn up well above the level of the mould (for approximately three centimetres).

The bowl is of the type also conventionally known as ‘Megarian’. The practice of making bowls in a mould rather than throwing them by hand seems to have been first introduced into the range of fine wares in Athens in the later part of the third century BC with the aim of imitating luxury silver-ware: see especially Susan I. Rotroff, “Silver, Glass, and Clay: Evidence for the Dating of Hellenistic Luxury Tableware”, Hesperia 51, 1982, 329-337; ead., “The Introduction of the Moldmade Bowl Revisited: Tracking a Hellenistic Innovation”, Hesperia 75, 2006, 357-378. The practice of making drinking vessels in this fashion spread fairly rapidly and was to last until well on in the Roman period in so-called terra sigillata. One advantage of the technique was that, once the mould had been made, bowls could be turned out in quantity and therefore more cheaply by relatively unskilled personnel. Over time, there was a natural reluctance to replace moulds as they began to show signs of wear and the quality of finish also tended to deteriorate.

On relief bowls in general, see the excellent survey by G. Siebert, “Les bols à relief. Une industrie d’art de l’époque hellénistique”, in: P. Lévêque and J.-P. Morel (eds), Céramiques hellénistiques et romaines (Ann.Lit.Besançon no. 242, Paris 1980) 55-84.

For more detailed studies of relief bowls from particular areas, see for example U. Hausmann, Hellenistische Reliefbecher aus attischen und böotischen Werkstätten. Untersuchungen zur Zeitstellung und Bildüberlieferung (Stuttgart 1959), id., Olympische Forschungen 27. Hellenistische Keramik (Berlin 1996), K. Parlasca, “Zur hellenistische Reliefkeramik Kleinasiens”, Bulletin Antieke Beschaving 57, 1982, 76-181, A. Laumonier, Exploration archéologique de Délos, xxxi. La céramique hellénistique à reliefs, 1. Ateliers ‘ioniens’ (Paris 1977), S.I. Rotroff, The Athenian Agora xxii. Hellenistic Pottery, Athenian and Imported Moldmade Bowls (Princeton 1982), J. Schäfer, Hellenistische Keramik aus Pergamon (Pergamenische Forschungen 2, Berlin 1968), G. Siebert, Recherches sur les ateliers de bols à reliefs du Péloponnèse à l' époque hellénistique (Paris 1979).

Moulds for relief bowls are found not infrequently. For a number of examples, see Rotroff’s Agora volume or G. Kleiner, “Zwei Formschusseln für megarische Becher”, in: Wandlungen. Studien zur antiken und neueren Kunst Ernst Homann-Wedeking gewidmet (Waldsassen 1975) 217ff. for a Pergamene and a Knidian example.

The vase was classified as being of mainland manufacture in Monuments Illustrating New Comedy (3rd ed. rev. and enlarged by J.R. Green and Axel Seeberg, BICS Suppl. 50, 1995), but, to judge by the clay, it is perhaps more likely that it is East Greek. It is to be dated in the second century BC, probably the later part, but it is difficult to be precise, especially given the worn nature of the mould - it may have been in use for some time. In terms of theatre-related material from east of the Aegean, one may note Rotroff’s publication of an imbricate bowl which has on the bottom a mask of wavy-haired slave (27) of remarkably mainstream appearance. Even if it was copied directly off imported material, it is interesting that a potter in Sardis at this date found the theme worth producing for his local market: S.I. Rotroff, “Moldmade Relief Bowls from Sardis’, in: Δ' Επιστημονική Συνάντηση για την ελληνιστική κεραμική: χρονολογικά προβλήματα, κλειστά σύνολα - εργαστήρια; πρακτικά [Μυτιλήνη, Μάρτιος 1994] (Athens 1997) 365 no. 7, pl. 266. The piece also appear in S.I. Rotroff and A. Oliver, Jr., The Hellenistic pottery from Sardis: The Finds through 1994 (Cambridge, Mass., 2003) no. 427, pl. 71. Rotroff includes there a number of comparable bowls together with further references: see under no. 420.

For another relief bowl with comic slave mask on the bottom, see Berkeley, Lowie Museum 8/4999, Poseidon’s Realm (Exhib.Cat., Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, 1982) 93 no. 80 (ill.); the outside has acanthus leaves and dancing figures.

The use of a theatre mask, and in particular that of a slave from comedy, is an appropriate motif for a drinking vessel. Not only was there a direct link with Dionysos who, as well as being god of wine, was god of theatre, but the mask itself carried the idea of festivity deriving from the parties in honour of the god after a successful performance in the theatre when the masks were dedicated in his sanctuary. The particular choice of the mask of a slave, and particularly that of the wavy-haired slave (mask 27) who was often characterised as enjoying wine himself, was doubtless based on the popularity of this figure on the stage and the way that he seems to have come to typify comedy with the public at large: compare the figurine 1979.05 where we see just such a character. For a fuller discussion of the role of theatre in Hellenistic society, see J.R. Green, “Théâtre et société dans le monde hellénistique. Changement d’image, changement de rôles", in Realia. Mélanges sur les réalités du théâtre antique. Cahiers du Groupe Interdisciplinaire du Théâtre Antique 6, 1990/1991, 31-49, and Theatre in Ancient Greek Society (London 1994), especially chapters 4 and 5.

Charles Ede Ltd (London) Antiquities 117 (1980) no. 46; Monuments Illustrating New Comedy (3rd ed. rev. and enlarged by J.R. Green and Axel Seeberg, BICS Suppl. 50, 1995) ii, 174, 3BV 3.