Collections:

Description:

Writing

Introduction by J.R. Green

There can be no doubt that the invention of writing has been the greatest single contribution to the development of civilisation, for the simple reason that it has allowed the recording and therefore the accumulation of information. The development of what we call literature was a secondary stage in the use of writing, but it was vitally important. It encouraged analytical thought inasmuch as narration very quickly gave rise to examination of the motives of the action narrated, and as description of phenomena moved to attempts to order and classify them.

Of all the writing systems, the alphabet as developed by the Greeks has proved the most efficient and simple to use. Indeed it has changed very little since it was first introduced, probably in the course of the eighth century BC. It was quickly transmitted by Greek colonists and traders to Italy where it was picked up by the Etruscans and eventually the Romans, and steadily developed into the Latin form we still use.

Among the earliest writing materials surviving are the baked clay tablets found in the Near East and in Bronze Age sites in Greece. These seem to have been used mainly for official records and writings of special importance and their circulation seems to have been limited - just as the ability to write seems to have been restricted largely to professional scribes. The Greeks and Romans used a very wide variety of materials depending to a large extent on the purpose involved. Our earliest surviving Greek inscriptions are found on pots where typically they signify the ownership of the vessel, but sherds could be used for casual purposes well down into the Roman period. (One may also note the Athenian practice of ostracism, named after the word ostrakon = sherd, in which the names of unpopular prominent citizens were written on sherds in a voting process to expel them from the state.) For official or public inscriptions intended to be permanent, the Greeks and Romans employed bronze tablets, slabs of stone or, especially in earlier times, whitened wooden boards. Of these, stone inscriptions have survived in the greatest number, and many of them have remained familiar objects since antiquity, particularly those incorporated in public buildings like the inscription on the architrave of the Pantheon in Rome.

The favoured material in the ancient world, especially for extended writing such as literary texts, was papyrus. When it was first used in Greece is debatable but it was certainly in relatively plentiful supply in Athens by the later part of the sixth century, although it was not inexpensive, being imported from Egypt. There is some evidence, for example, that playwrights wrote first drafts on waxed tablets and used papyrus only for the final version. Schoolboys too practised writing on waxed tablets. Nevertheless the supply of papyrus increased steadily during the classical period, as written texts too became more common, and by the turn of the fifth and fourth centuries, Xenophon (Anabasis VII.5, 12-14) seems to regard its use as being as typical of Greek culture as the symposion. As a material it is easy to write on, with a good smooth surface. It was used mainly in roll form (thus the word volumen in Latin), but in time and for some types of document, it came to be used in folded book form (codex). Its brittleness, however, made it unsuitable for this purpose. With improved methods of preparing animal skins, vellum eventually replaced papyrus as the standard material, and this was well suited to folding into codex form. The change to the codex between the second and fourth centuries AD was possibly hastened by the Christian need for a type of book in which it was easy to refer from one passage of Scripture to another, but in any case the introduction of the book as distinct from the roll was a major technological advance. Books were written on paper from about the twelfth century, although vellum continued to be used too until the printed book began to replace manuscripts from the second half of the fifteenth century AD.

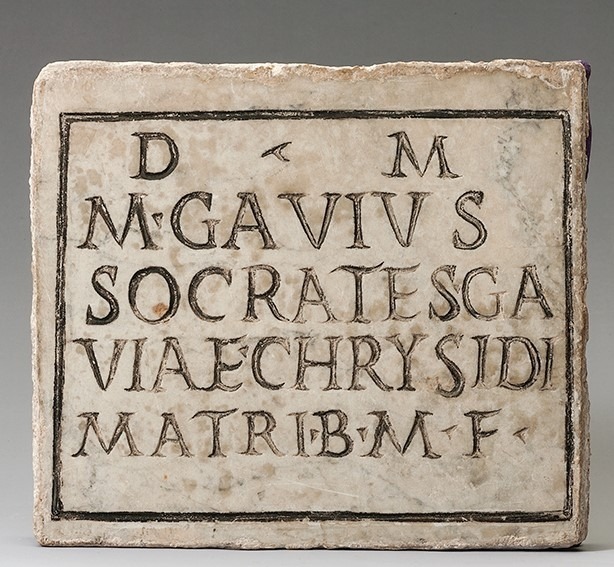

The collection contains a good number of objects which have writing on them. The Attic black-figure cup, 1965.15, has a nonsense inscription as part of its decoration. The black-glaze askos, 1965.03, has the graffito of an abbreviation of the owner’s name scratched on the underside. The grave stele, 1978.01, of the late fifth century BC created a permanent record of the name of the woman and her two daughters who were buried in the grave with her. See also the Phrygian grave relief, 1989.01 and the hero relief 2013.03. The Roman lamp, 1978.08, and the bowl, 1985.13, have the makers’ names stamped on the underside. The marble cinerary urn, 1979.03, gives the details of the deceased. This present section includes a range of other materials, such as makers’ stamps on amphorae and bricks, other funerary inscriptions, papyri, wax tablets and then manuscripts on vellum and paper.

On early inscriptions and the development of the Greek alphabet, see J.F. Healey, The Early Alphabet (London 1990), L.H. Jeffery, Local Scripts of Archaic Greece (2nd ed., rev. A.W. Johnston, Oxford 1988), and then H.R. Immerwahr, Attic Script. A Survey (Oxford 1990). More generally, see A. Morpurgo Davies, “Forms of Writing in the Ancient Mediterranean World”, in G. Baumann (ed.), The Written Word. Literacy in Transition (Oxford 1986) 51-77 and J.T. Hooker et al., Reading the Past. Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet (London 1991). Another excellent introduction is M.P. Brown, A Guide to Western Historical Scripts from Antiquity to 1600 (London and Toronto 1990); it also contains a good bibliography. Also P.T. Daniels and W. Bright (eds.), The World's Writing Systems (Oxford 1996). For a good and comprehensive survey of depictions of reading, writing, book-rolls and writing instruments in fifth-century Athens, see A. Chatzidimitriou, “Η γραφή και η ανάγνωση στην εικονογραφία των αρχαϊκών και κλασικών χρόνων”, Archaiologikon Deltion 67-68, 2012-2013, 305-368 (with English summary on p. 368).

On book rolls, H.R. Immerwahr, “Book Rolls on Attic Vases”, in: C. Henderson (ed.), Classical, Mediaeval and Renaissance Studies in Honor of Berthold Louis Ullman (Storia e Letteratura 93, 1964) i, 17-48, and “More Book Rolls on Attic Vases”, Antike Kunst 16, 1973, 143-147, E. Pöhlmann, “Die Notenschrift in der Überlieferung der griechischen Bühnenmusik”, Würburger Jahrbücher für die Altertumswissenschaft. Neue Folge 2, 1976, 53-73, pll. 1-2 (= Beiträge zur antiken und neueren Musikgeschichte, Frankfurt 1988, 57-93). There is also a very useful series of illustrations in F.A.G. Beck, Album of Greek Education (Sydney 1975).

On what little we know of the cost of papyrus, see N. Lewis, Papyrus in Classical Antiquity (Oxford 1974) 129-134, and Papyrus in Classical Antiquity. A Supplement (Brussels 1989) 9 and 40. For recent discussion of writers’ working methods, see T. Dorandi, “Den Autoren über die Schülter geschaut: Arbeitsweise und Autographie bei den antiken Schriftstellern”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 87, 1991, 11-33; W.J. Tait, “Rush and Reed. The Pens of Egyptian and Greek Scribes”, Procs XVIII Int Congr Papyrology ii (Athens 1988) 477-481. Note the bronze stylus for writing on wax, 1980.01, elsewhere in this cataologue and D. Bozi and M. Feugère, “Les instruments de l’écriture”, Gallia 61, 2004, 21-41. For the ink used, see T. Christiansen, “Manufacture of Black Ink in the Ancient Mediterranean”, Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 54, 2017, 167-195; J. Eiseman, “Classical Inkpots”, American Journal of Archaeology 79, 1975, 374.

On books and writing in general, E.G. Turner, Athenian Books in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries B.C. (London 11951, 21977), B.M.W. Knox and P.E. Easterling, “Books and Readers in the Ancient World”, P.E. Easterling, E.J. Kenny (eds), The Cambridge History of Classical Literature, i. Greek Literature i (Cambridge, 1985), 1-41 and the useful review by G. Cavallo, “Storia della scrittura e storia del libro nell’antichità greca e romana. Materiali per uno studio”, Euphrosyne 16, 1988, 401-412 (esp. 407f.); W. Clarysse and K. Vanorpe, “Information Technologies: Writing, Book Production, and the Role of Literacy”, in: J.P. Oleson (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World (Oxford 2008) 75-739. For later developments, L.D. Reynolds and N.G. Wilson, Scribes and Scholars. A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature (3rd ed., Oxford - New York 1991) is especially important. See also E.G. Turner, Greek Papyri. An Introduction (Oxford 1980) and Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World (2nd ed., rev. P.J. Parsons, BICS Suppl. 46, 1987), A. Bowman and J.D. Thomas, Vindolanda: The Latin Writing Tablets (Gloucester 1984), F. Arduini, The Shape of the Book: from roll to codex (3rd century BC-19th century AD) (Florence 2008), B. Harnett, “The Diffusion of the Codex”, Classical Antiquity 36.2, 2017, 183-235. On the material from Vindolanda, there is now Vindolanda Tablet Online 1 and 2. The remarkable collection of tablets from Vindonissa in Switzerland was published by M.A. Speidel, Die römischen Schreibtafeln (Brugg 1996) together with a careful commentary and discussion. For our earliest preserved Greek writing tablet, from a remarkable grave at Daphne, see M.L. West and E. Pöhlmann, “The Oldest Greek Papyrus and Writing Tablets: Fifth-Century Documents from the ‘Tomb of the Musician’ in Attica”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 180, 2012, 237-247. For examples of writing on skin from the second century bc: W. Clarysee and D.J. Thompson, “Two Greek Texts on Skin from Hellenistic Bactria”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 159, 2007, 273-279.

For libraries, including the phenomenon of the great library at Alexandria, useful sources include L. Casson, Libraries in the Ancient World (New Haven 2001), G. Cavallo (ed.), Le biblioteche nel mondo antico e medievale (Bari 2008).

On the styles of Greek written script, there is an interesting paper by Alan Johnston, “Straight, Crooked and Joined-up Writing: An Early Mediterranean View”, in: K.E. Piquette and R.D. Whitehouse (eds), Writing as Material Practice: Substance, Surface and Medium (London 2013) 193-212. For another clear and fully reliable source, see P. Easterling and C. Handley, Greek Scripts. An Illustrated Introduction (London 2001).

For the importance and impact of writing and the change from oral to literate culture, see in particular J. Goody and I. Watt, “The Consequences of Literacy”, in J. Goody (ed.), Literacy in Traditional Societies (Cambridge 1968) 27-69, J. Goody, The Domestication of the Savage Mind (Cambridge 1977), W.J. Ong, Orality and Literacy. The Technologizing of the Word (London 1982), E.A. Havelock, The Literate Revolution in Greece and its Cultural Consequences (Princeton 1982) and The Muse Learns to Write (New Haven 1986), M. Detienne (ed.), Les savoirs de l’écriture en Grèce ancienne (Lille 1988), A. Burns, The Power of the Written Word. The Role of Literacy in the History of Western Civilisation (New York 1989), M.L. Lang, “The Alphabetic Impact on Archaic Greece”, in: D. Buitron-Oliver (ed.), New Perspectives in Early Greek Art (Studies in the History of Art, 32, Washington DC 1991) 65-79, M. Beard et al., Literacy in the Roman World (JRA Suppl. 3, Ann Arbor 1991); B. Powell, Writing: Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization (Chichester 2009). For the place and function of writing in the development of Athenian democracy, see D. Musti, “Democrazia e scrittura” Scrittura e Civiltà 10 (1986) 21-48 and R. Thomas, Oral Tradition and Written Record in Classical Athens (Cambridge 1989); also W.V. Harris, Ancient Literacy (Cambridge Mass., 1989); H.J. Graff, The Legacies of Literacy in the West (Bloomington, Indiana, 1987); W. Rösler, “Books and Literacy”, in: G. Boys-Stones, B. Graziosi and Ph. Vasunia (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies (Oxford 2009) 432-441. On inscriptions from the Roman world, C. Bruun and J. Edmondson (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy (2014) is now a vital starting point.

On the broader context of writing systems, see the essays collected in J.T. Hooker et al., Reading the Past. Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet (Berkeley 1991).

Other useful items are mentioned under individual entries below.

Stamped Amphora Handles

1970.06 - 1970.09

Funerary Inscriptions

On the reception and treatment of inscriptions from the ancient world, there is an excellent collection of papers in Alison E. Cooley (ed.), The Afterlife of Inscriptions: Reusing, Rediscovering, Reinventing & Revitalizing Ancient Inscriptions (BICS Supplement 75, London 2000).

On the role of writing more generally in Rome, and especially its place on public monuments, one should note particularly M. Corbier, Donner à voir, donner à lire: mémoire et communication dans la Rome ancienne (Paris 2006).

For an interesting introduction to the uses of such inscriptions in telling us about the people whom they recorded, see B.K. Harvey, Roman Lives: Ancient Roman Life as Illustrated by Latin Inscriptions (Newburyport, MA, 2004). Somewhat similar in its aims is an excellent overview by A. Kolb and J. Fugmann, Tod in Rom: Grabinschriften als Spiegel römischen Lebens (Mainz 2008). Note also B.W. Frier, “Roman Demography”, in: D. Potter (ed.), Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire (Ann Arbor 1999) 85-112. At a broader level, dealing with more official inscriptions, L. Keppie, Understanding Roman Inscriptions (London 1991). And then, particularly on slaves and their circumstances, K. Hasegawa, The Familia Urbana during the Early Empire: a Study of Columbaria Inscriptions (BAR S1440, Oxford 2005). On these tombs as reflections as communities of people, D. Borbonus, Columbarium Tombs and Collective Identity in Augustan Rome (Cambridge 2013).

1971.03 - Marble Funerary Inscription

1971.04 - Double-Sided Marble Funerary Inscription

2002.12 - Fragment of an Inscription on Marble

Other Writing Materials

1973.01 - Writing Tablet

1975.01 - Fragments of Papyrus Document

1977.06 - Manuscript of Cicero’s Epistulae ad familiares

1978.03 - Manuscript of Gasparino Barzizza’s Orthographia, etc.

1980.01 - Stylus

1991.03 - Ostrakon

2006.01 - Tablet inscribed in cuneiform