Collections:

Description:

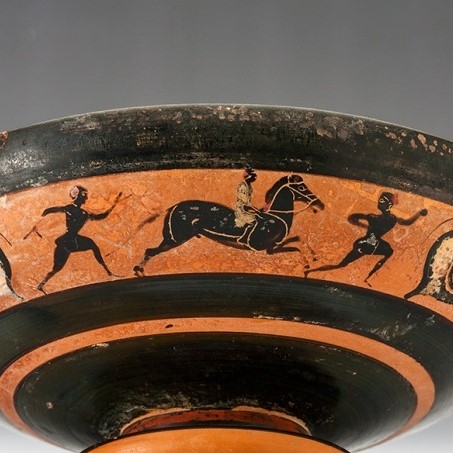

Pottery

Introduction by J.R. Green

Of all the categories of archaeological material, pottery must rank as the most important. From its introduction in the Neolithic period until recent times when plastics and readily-manufactured metals have replaced it for some functions, it was the most commonly used container, especially for liquids, and more efficient or easily made than some ‘natural’ products such as wood or basketry. lt was a fairly inexpensive commodity which, when broken, could be replaced without too much hardship. When broken it is virtually useless and has no value as scrap in the way that metal can be melted down and re-used, or marble, at the very worst, converted into lime. It is also difficult to destroy and so tends to be preserved in relatively large quantities. At least from the time the wheel was introduced for its manufacture, pottery was produced by specialists rather than by individuals in the home, and as a consequence it became relatively standardised in its forms, while at the same time reflecting the changing needs of the society for which it was produced. It is therefore susceptible to classification on chronological and other bases. Some societies, not least Greek, were wealthy enough to allow other considerations to come into play: a high degree of specialisation in the function of vessels (reflected in the very wide range of shapes) and, perhaps more importantly for our purposes, sophisticated decoration which at times brought a transition from simple craft to art. From the eighth century bc, the Greek preoccupation with the depiction of the human figure was reflected in pottery decoration and from then until the later part of the fourth century bc, a growing proportion of the ‘better’ Greek pottery was decorated with human figures. We can therefore see on their pottery how they conceived their life, their myth and their gods; we can see too, at least until the mid-fifth century, the steady movement towards naturalistic and three-dimensional representation which the Greeks made the foundation of western art. Nonetheless, Greek pottery was always functional and was primarily designed in functional terms. The concept of the art-object did not arise where pottery was concerned.

Of the general books on Greek pottery, P.E. Arias and M. Hirmer, A History of Greek Vase-Painting has good illustrations with careful and detailed notes by B.B. Shefton. R.M. Cook’s Greek Painted Pottery (3rd ed., London 1997) gives a neat and carefully considered survey of the various classes and local styles as well as a most useful history of the study of vase-painting. Lively and useful brief introductions have also been provided by D. Williams, Greek Vases (2nd ed., London 1998) and Brian A. Sparkes, Greek Pottery. An Introduction (Manchester 1991). There is also much to be learned from the articles in T. Rasmussen and N. Spivey (eds.), Looking at Greek Vases (Cambridge 1991). Most books, however, are concerned with vase-painting rather than pottery, and shapes have been treated much less satisfactorily. Still regarded as standard for pottery of the classical period, though badly out of date, is G.M.A. Richter and M.J. Milne, Shapes and Names of Athenian Vases (New York 1935). M. Kanowski, Containers of Classical Greece: A Handbook of Shapes (St. Lucia, Queensland, 1984) is a useful guide for students.